North Walsham in the 19th Century

Index.

- FOREWORD

- THE LATEST FASHIONS

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 1 - North Walsham mid 19th Century

- Chapter 2 - A Young Society

- Chapter 3 - The North Walsham and Dilham Canal

- Chapter 4 - Bluebell and Spa Commons

- Chapter 5 - Assisting the poor

- Chapter 6 - Poverty & Protest: The Agricultural La

- Chapter 7 - Crime and Punishment

- Chapter 8 - The Fisher Theatre

- Chapter 9 - North Walsham Celebrations

- Chapter 10 - The Impact of Religion

- Chapter 11 - Education in North Walsham

- Chapter 12 - The Railway come to North Walsham

Education in North Walsham

Copy of drawing made c. 1827 by J. B. Ladbrooke by Sheila Watson

The oldest established school in North Walsham in the 19th century was the Paston School which was founded and endowed as a Free Grammar School in 1606 by Sir William Paston for the instruction of 'forty sons of the inhabitants of the hundreds of Tunstead, Happing, North Erpingham and East and West Flegg.' Sir William believed the school would help to discipline the youth of the area, whom he felt had 'over-much liberty'. In addition to teaching grammar, boys would be taught 'good manners, learning and true fear, service and worship of Almighty God, whereby they might become good and profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth.' The Master's house was re-built in 1796 and other additions and alterations were made to the school during the 19th century.

In the earlier period senior positions in education were, by custom, filled by men in Holy Orders, although this was not a necessary qualification. In the 19th century the eight masters who were in charge of Paston School were all clergymen of the Church of England.

Paston School, like many schools endowed to provide free education for local boys, gradually took more fee-paying pupils and free places declined. In fact, by 1813 the school was entirely supported by fee-paying boys. The school was, however, compelled to re-introduce free pupils, for which the school was originally established. A governors' meeting in 1813 recorded a Minute requiring 'that the 40 free boys ... to be selected in equal numbers' from the original catchment area and that no boy was to be admitted into the school without a Presentation signed by three of the school governors residing nearest to North Walsham.

The then Master, the Rev. William Spurdens (who was master at the school from 1807 until 1825) was less than appreciative of this move. He later complained in a letter to the governors that he had not been told he had to teach forty free boys nor had he 'ever heard of such an obligation' in the seven years he taught there before he became master. He complained that if he had known this he might have hesitated to apply for the post. He also stated 'I was certainly much surprised when the late Mr. Petre, offended at a peccadillo of one of my pupils, first threatened to enforce the Statutes of the School and send me forty free boys.' It would seem, therefore, that the re-introduction of free pupils may well have come about as a result of the actions of Mr. Petre of Westwick Hall. Some of the parents of boys at the school appear to have held the same opinion of free scholars being brought into the school as Mr. Spurdens who went on to report that although the full number of forty free pupils was not sent, the numbers of fee-payers in the boarding school went down as soon as free boys were admitted. He reported notices for 23 removals, 17 of which stated that the reason for leaving was due to the admission of free pupils. However, it seems that free scholars did not become significant in the school. In 1832 there were only six although, according to the Charity Commissioners, some of the 56 boarders were given some reduction in fees. In 1845 it was reported that there were 'seldom more than 8-10 free boys'. Fee payers in this period, paid £50 a year.

Free places were almost certainly filled by children from better-off families since poor families were unable to afford the 'extras' and the loss of earnings by allowing their children to stay on at school. A free place did not provide free tuition in all subjects. The report of the Charity Commissioners, published in 1836, stated that at Paston School - 'Scholars are taught Latin and Greek and also algebra, mathematics and English history without any charge but for instruction in writing and accounts it has been usual to charge 8gns a year'. In addition 30s each half year was charged for books, stationery and heating.

Little is known about the provision of comfort and welfare of the boys. Boarders lived in the schoolhouse with the master and a matron was responsible for their welfare. In the middle of the century Thomas Dry was master of the school living in the schoolhouse with his wife, four daughters and one son. In addition to the matron, other living-in staff comprised a cook, two housemaids and a young boy servant. It is possible that daily staff may also have been employed, particularly on wash-days!

By the 1850's the number of pupils had declined and the family sometimes out-numbered the boarders in the schoolhouse! It seems that by this date the standard of education provided at the school had deteriorated and pupil numbers continued to fall in the following decade. The Norfolk Chronicle, reported early in 1874, that the school, some years previously, had decayed until there remained only the master and no scholars. In 1869 the Report of the Taunton Commission, set up in 1864 to Enquire into the State of Endowed Schools in England and Wales, concluded that Paston School could no longer succeed as a classical school. It was said that the 'better classes' sent their children to larger schools and the poorer did not want Latin.

The Endowed Schools Act, which was passed as a direct result of the Taunton Commission, appointed special Commissioners to reform endowed schools and it was under the Commissioners that Paston School was re-organised and the building renovated. The curriculum still included Latin and Greek but greater emphasis was to be given to mathematics, history, geography, natural science and drawing and other subjects were added. The Rev. Frederick Pentreathe was appointed master and Mrs. Pentreathe was in charge of 'domestic comforts' of the boarders. The School opened on the 24th February 1874 with 11 boys; after the Easter vacation the number had increased to 31. Further improvements in accommodation took place towards the end of the 19th century including the building of a science laboratory and a gymnasium. By 1904 the school had 34 boys.

There had, in the past, been some difficulties with clerical heads of the school taking on the responsibilities of several parishes in addition. The Rev. William Spurdens had, at one time, held the cure of several parishes whilst Master of Paston School. Under the new scheme formulated for the school in 1873 it was laid down that the head, who need not be in Holy Orders, was not to hold other employment. The tradition of a clerical head persisted, however, as the Rev. Frederick Pentreathe was Master from 1874 - 78. By the beginning of this century a non-cleric was headmaster.

Paston School's most famous pupil was Admiral Lord Nelson, who was born in Norfolk, at Burnham Thorpe, and attended the school for two years before joining the Navy when he was twelve years old. A school's worth, however, should not be judged by its famous pupils alone. After the transformation of the school by Rev. Frederick Pentreathe it became an academic and sporting institution which continued to contribute to the life of the county until, in 1984, 378 years after its foundation, it became a sixth form-college.

Sources:

Reports of the Charity Commissioners, Norfolk, 1815-1839, N.L.S.L. W.White's 1845 Norfolk Directory. Norfolk Chronicle 1874

C. D. Forder, A History of the Paston Grammar School, 2nd Edition, 1975. Census Return 1851.

Private Schools

In addition to a parish school and the endowed Paston School a number of 'private' fee-paying schools were opened in the town during the nineteenth century. Most were small establishments and most were short-lived. North Walsham, like many small market towns, had several schools described as 'day and boarding schools', as children from the surrounding area needed to board since lack of transport made it difficult to attend on a daily basis.

What standards of education these schools gave is, unfortunately, not known due to the absence of documentary records. It is likely that most offered a fairly basic syllabus, consisting of reading, writing and arithmetic. Some were, no doubt, dame schools, which were, as a rule, little more than child-minding establishments being set up by failed tradespeople or elderly ladies. Nevertheless, some of the schools which opened in the town may well have provided a more advanced curriculum together with those refinements considered necessary for young ladies and gentlemen in this period such as dancing, deportment, French and embroidery for girls.

In July 1803 there was an advertisement in the Norwich Mercury for what appears to be a boarding school as washing was included in the fees.

"North Walsham Academy - T. Dix begs leave to inform the public that he intends opening an Academy at North Walsham on Monday next, July 18th., and proposes teaching the most useful branches of English education. Terms:- 20gns a year including washing and all other charges, except stationery articles. Entrance 1gn".

Whether Mr. Dix's academy was ever formed is not known. There is no mention of it in any Directories and no further advertisements have been found.

Piggott's Directory shows there were five private schools in the town in 1830; of these, only John Crickmore's boarding school, in Free School Road and Sarah Saul's school for 'young ladies' remained by 1835 although the number of schools had not decreased since three new ones had opened. One had been set up by the Rev. James Browne in Chapel Street, Mary Ann Pope had a school in The Market Place and Amy Clements ran a boarding school, the address of which is not known. White's Directory shows that by 1845 some of these schools had closed and new ones had replaced them. There were seven private schools at this date. These were -

The Rev. James Browne's school, now in Antingham Road.

Mary Ann Davidson, Chapel Street (is this Mary Ann Pope, now married?).

William Wiggett, Low Street.

Joseph Webster, Reeves Lane.

Samuel Blyth, boarding school, Low Street.

Miss Sophia Cross, boarding academy, North Street.

Sarah Saul's school, also a boarding academy, had been taken over by Harriet Simpson and her daughter Sarah.

In 1846 a Miss Sarah Browne is found running a school in Antingham Road and it seems very likely that she is the daughter of James Browne, who is now excluded from the list. By 1858 Sarah, herself, is no longer in charge and it seems that a Miss Sarah Fitt has taken over this school, now described as a 'seminary and boarding school' at Belle Vue House in Antingham Road. Miss Fitt also described herself as ' a modeller of wax flowers and ornamental Ieatherwork on frames, baskets, etc' By the mid-sixties Sarah's sister was assisting with the running of the school; it seems to have closed some time during the following decade.

Despite several schools being described as boarding schools the 1851 Census Return shows that only three schools in the town had boarders at that date. They were Paston School, the Simpson's School and the school run by Miss Sophia Cross which had now moved to Yarmouth Road. This school had moved again, by 1863, to King's Arms Street.

In addition to the provision of education for the young, people of all ages in North Walsham could take the opportunity of further education or acquire a new skill (providing they were able to pay) from tutors who advertised within the town. Tuition was given in a variety of subjects including languages, dancing, drawing, music, navigation and writing. William Smith, in the Market Place, for example, offered tuition in French in the middle of the century and John Mower, the bookseller and stationer, also advertised as a teacher of music.

In the sixties Mrs. Elizabeth Webster ran a seminary in White Lion Lane. It is sheer speculation to suggest she was possibly the wife or, more likely, the widow of Joseph Webster, who ran his own school in North Walsham fourteen years previously.

Schools continued to open and close during the second half of the century. During the 1860's there seem to have been five private schools in the town of various kinds; in 1883 there were six - one of which, Mrs Hindry's school at 4, The Terrace, advertised as a dame school. This is the only school of this type found although there were, no doubt, others. By the end of the nineteenth century only three private schools seem to remain. These were Miss Elizabeth Hunter's 'private girls school' in The Terrace. Miss Rae's 'girls' private school', Norwich Road, and the school belonging to the Miss Cookes.

Of the numerous schools set up during the nineteenth century only three survived over a period of time. The earliest reference to the Ladies Academy at 15, Aylsham Road, under Miss Sarah Saul, is found in Piggott's Directory of 1830. By 1835 Harriet Simpson and her daughter, Sarah, had taken it over and continued the academy for a number of years at the same address. In 1865 Kelly's described the school as being in Angel Street but this is because the name of the street had changed - it later reverted back to Aylsham Road! In 1841 there were eleven boarders at the school between the ages of 5 and 15 years old. In 1851, the number was down to six, although it is presumed there were day girls in addition. At that date Harriet Simpson was 73 years old, her daughter Sarah was still with her although it is found that a few years later Sarah was running the school alone. Harriet must have retired or, perhaps, had died. Sarah gave up the school sometime between 1865 and 1871 as an Elizabeth Ladell is recorded as proprietor in 1871, living at the school with her husband Richard and three sons. Mrs Ladell continued the school until 1883, when she is found in Kelly's Directory of that year, and perhaps for a few years after that but by 1896 the school had closed as one of her sons, Henry Richard, is found living at the address, which is described as a private house. Ivy Cottage, as it is called today, had been a school for young ladies for over fifty years during which time it must have been attended by many young girls in the neighbourhood.

Miss Sophia Cross had established her ladies school by 1845 in North Street and this too survived for many years in the town. By 1851 the school had moved to Yarmouth Road and by this time Sophia had been joined in the enterprise by her sister Lydia. By 1863 the school had moved again, to King's Arms Street, perhaps to a larger building. The sisters were still working in 1871 when Sophia was 65 and Lydia 61 and, like Harriet Simpson, it seems they worked until illness or old age forced them to retire. It may indeed, have been due to financial need rather than for pleasure that they worked so late in life for there was no state pension in this period to provide for a few comforts during their last years. It is believed the school closed sometime during the 1870's, it is not included in Kelly's 1883 Directory and Sophia, then aged 77 years old, was living in a private house in School Road by that time.

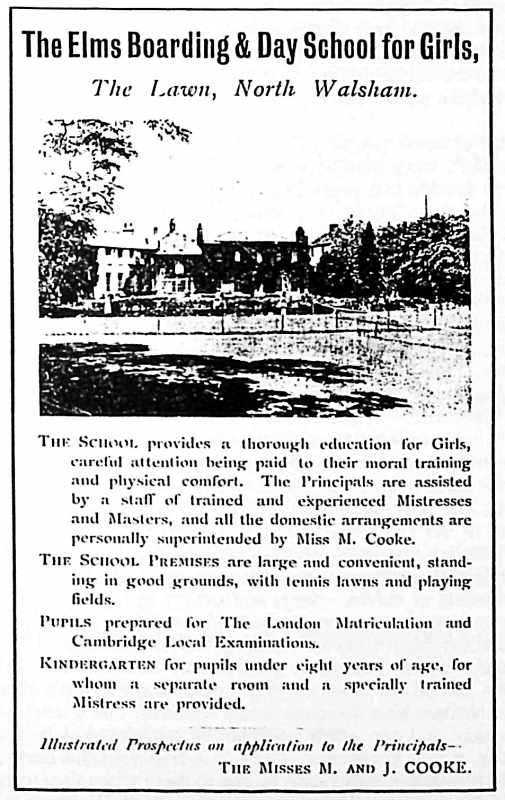

Another long-established school in the town and one which became significant for the education it provided was set up by the Misses Maria and Jane Cooke in 1877 and described as a 'small select ladies school'. This was established at Kyneton, a private house on the corner of Cromer and Mundesley Road. The school moved soon after to The Elms, North Street, where it remained until early this century. The type of education provided for middle-class girls had always been different to that provided for boys. Girls were not expected to become intellectuals but during the last quarter of the nineteenth century there was some concern that girls should have the opportunity of academic education and schools offering this were established in some areas. North Walsham was fortunate that The Elms was providing a higher standard of education for girls in the neighbourhood whose parents could afford to pay the fees which were, of course, beyond the reach of ordinary working families. The school, which employed specialist teachers, prepared the girls for matriculation which could lead to university and a professional career.

That there were fewer private schools at the end of the century when the population of North Walsham was almost double what is was in 1800 is not really surprising. This is a trend that took place in many towns. As more places in National and later,in Board Schools, were provided and standards of teaching rose in these schools there was less need for small private schools offering very basic skills. Moreover, when state education became free parents were generally unwilling to pay for such schools unless they gave an education the state did not provide. Thus, the number of these schools declined and, in the main, only the better private schools succeeded.

Sources:-

Norfolk Directories.

1851 & 1871 Census Returns.

Norwich Mercury.

(from North Walsham and The Broads. F. Bohn, 1911)

Sunday School to Board School.

At the beginning of the 19th century there was little education for children whose parents were unable to pay fees except for a few who gained places in endowed schools and charity schools. The main purpose of the Sunday Schools which were established was to teach children their Catechism and to learn to read the Bible.

A small school had been set up in North Walsham by the parish for poor children in the late 18th century. There are few details of this. A meeting in April 1795 agreed that the school should continue and the children who wished to attend were to be chosen by a committee who would also watch over the school. There are a few references to applications from parents wanting to send their children there and at a Vestry meeting in May 1800 a Decker Edinthorp applied for a pair of boots for his son that he might attend Mr. Trivett's school. He was granted the boots on the condition that the boy did attend the school. It is presumed that the school was kept up from the parish poor rate and, perhaps, donations.

The attitude of many people towards education for the poor was shown by David Giddy, M.P., who, when opposing a Bill proposed by Samuel Whitbread (the brewer) to provide two years free education to children in 1807, said that education to the poor.."would be prejudicial to their morals and happiness; it would teach them to despise their lot in life, instead of making them good servants in agriculture and other laborious employments."

Nevertheless, there were those who felt some type of schooling should be given to children of the poor which would instil moral and religious behaviour and that they should be taught to read. With this in mind, in 1810 Joseph Lancaster, a Quaker, founded the Royal Lancasterian Association, which, in 1814, became the British and Foreign Schools Society, a non-sectarian group where the religious emphasis was on Nonconformist lines. These schools were commonly called 'British schools'. Teaching was, at first, conducted on the monitorial system, that is, some of the older children were taught to teach the younger ones. A British School opened in North Walsham in Frere Road in 1847.

An Anglican society, with a similar teaching system, was formed about much the same time; The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, usually referred to as The National Society and their schools 'National' schools. The Society was founded in 1811 and a Norfolk Branch inaugurated the following year in 1812, at a 'numerous and respectable meeting of nobility, clergy and gentry' in Norwich. The aim of the Society was to instruct the poor in 'suitable learning' and where it was not possible to establish day schools to encourage Sunday Schools. The schools were not free, usually parents paid on a graded scale of about Id - 2d a week for poorer families and 3d for those earning more. Some schools charged less per child if several children from the same family attended. The Society saw education as a 'patriotic duty' and one which could not be considered without the Christian faith. One was, it was considered, more of a friend to the poor if they were helped to help themselves rather than to give to them when they were in distress.

A 'National' Sunday School had been set up in North Walsham by 1813. It is most likely that this took over the parish school described, if indeed it still existed at that date, since no further records have been traced. The school was held in a large room in the workhouse superintended by a Mr. Hay. There were 150 pupils on the register made up of 67 boys and 83 girls. By 1815 the school also met one day during the week but the number attending was now only 89-51 boys and 38 girls. The school was described as 'extensive by 1818 and was meeting two days in the week to teach the girls needlework, in addition to Sundays. The Vicar, the Rev. W. F. Wilkinson felt that the poor of North Walsham were not ' without means of education'. By 1827 the school was meeting in the parish church and in addition to the Sunday school sewing was taught on three half days each week. There were two teachers, William Moyes and Susanna Pope to manage 33 boys and 45 girls. The youngest children at the school were five years old and the eldest 12 and 14 years of age.

Voluntary Visitors inspected the school, generally on an annual basis to test the childrens' progress. A Visitors Report of North Walsham school, written in 1827, shows the emphasis placed on learning to read the Bible.

------------------------------------------------------

NORTH WALSHAM SCHOOL (supported by subscriptions)

Visitors Report 25th July, 1827.

BOYS

Class 1 (8)* Spelling, Graces and prayers, Collect all perfect.

Catechism better "if not in too much of a hurry."

Bible reading good.

2 (6) Reading and Spelling from Old Testament tolerably well.

3 (5) Spelling words of 5 letters nearly perfect.

4 (5) Imperfect Prayers and spelling.

5 (4) Learning alphabet, Lord's prayer perfect.

GIRLS

Class 1 (8)' Read Old Testament very well, Catechism, Collect all perfect.

2 (10) Read New Testament well, Spelling, Catechism and Collect

all perfect.

3 (9) Read 1st book very well, Catechism 6 perfect 3 imperfect.

4 (5) Catechism imperfect.

5 (6) Learning alphabet.

The girls are taught sewing three times in the week.

Note: ' number of children in class.

Class 1 was the "top" class and Class 5 the infants.

------------------------------------------------------

It was in 1833 that the first grant towards education was made by government; this was towards the building of schools but the Voluntary Societies (i.e. the National and British societies) had to raise half of the cost first before applying for a grant. From 1840 more financial aid from government was granted, generally in relation to what was raised voluntarily. Moreover, from this date standards gradually improved as Inspectors were appointed to inspect schools which accepted government grants. A pupil teacher training scheme was implemented, where young girls could train in the classroom; a few were fortunate enough to go to training college. Emphasis was placed on teaching the '3 RV - reading, writing and arithmetic. It was not until later in the century that P.T. (physical training) and recreational subjects were generally introduced in elementary schools.

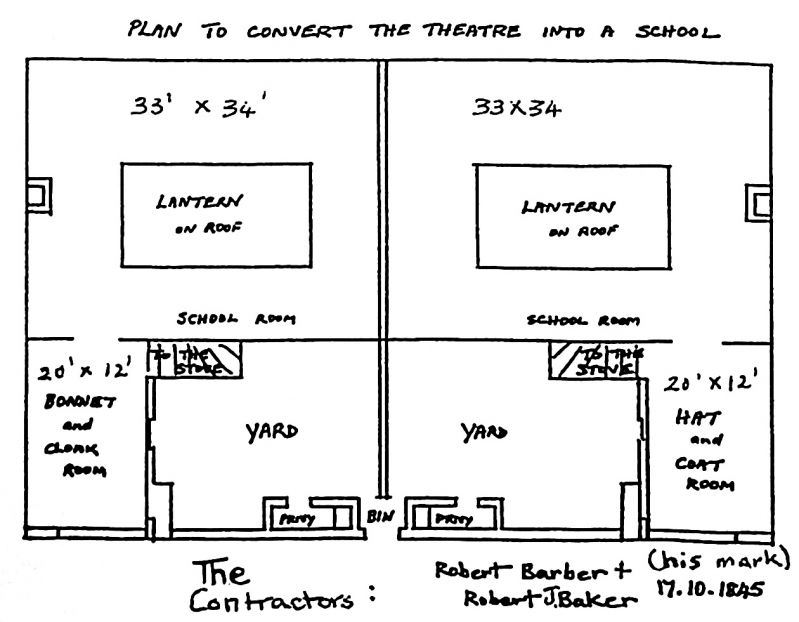

It must have been difficult to organise the school in North Walsham church but it continued there until 1845 when the former Fisher Theatre in Vicarage Street was bought and adapted as the National School. It is very likely that the money was raised by donations and a government grant. The building was described, after alterations as a 'large and commodious school capable of accommodating between 200 - 300 children' but how many children were on the register at this time is not known. It seems there was just a staff of two. A Mr. Charles Feltham was master and his wife mistress. Mr. Feltham was still in charge 13 years later, in 1858. Another married couple, Mr. Jonathan and Mrs. Margaret Badcock were in charge in 1865. Unfortunately, no records of the school in this period seem to survive.

According to the Norfolk Chronicle the children had an annual treat. On the 3rd October 1863 it was reported that the children of the National Day and Sunday School had their annual treat with a dinner in the schoolroom and ' by the liberality of Mr. Samuel Sewell, farmer, who kindly loaned his horses and "five wagons, had a visit to Mundesley in the afternoon ' The children, it was said, enjoyed the sea air and returned to the schoolroom for tea; ' all enjoyed a happy day. Indeed, for many children this must have been an exciting day and the only time in the year they visited the seaside.

In the middle of the century there were about 590 children in North Walsham between the ages of 5 and 13 years of age, although not all of these children would have attended school. The Rev. W. Wilkinson complained, in 1838, that 'the agricultural population do not attend to the education of their children' but working life began early for most of these children and poor parents needed the income they could bring in, however meagre.

It is usually found that many of those on the school register attended far from regularly. Sickness, bad weather and seasonal work kept children away and sometimes girls were kept at home to look after younger children so that mothers themselves could go out to work. The Summer vacation took place as soon as the harvest began since few would have attended school at a time when there was work for most of the family. Many Norfolk schools closed for a week or so in the Autumn when the children went acorn gathering.

The cost of building and maintaining schools was considerable and was a continuing burden for the voluntary societies. The National Society held a meeting in North Walsham in the autumn of 1863 when it was stated the Society had helped to establish hundreds of schools. Nevertheless, it needed more help 'from the wealthy classes of the county' and thanked all those who helped to support the school in the town in the past. At the close of the meeting a collection was taken towards their work.

In 1870, under Forster's Act, the government took responsibility to provide and maintain schools under School Boards where the voluntary sector could not do so. It was under this Act that an elementary school was built for the children of North Walsham in Manor Road replacing the converted buildings in Vicarage Street. The school, made up of three departments, opened in 1874. Children who attended on the opening day were given a bun and an orange. This school soon became too small, it was enlarged and altered four times in the next few years - 1888, 1892, 1897 and in 1899!

School attendance did not become compulsory under Forster's Act; nor did it become free. In 1880 attendance was made compulsory on a full time basis with a minimum leaving age of 10, if 'proficient'; if not, the child stayed until 13. Part-time attendance was allowed between 10 and 13 years of age. In 1891 elementary education became free.

Sources:-

N. Walsham Town Minute Book, Parish Papers

Visitors' Reports C/ED 3/211, 212, N.R.O.

Articles of Inquiry. ND Records, N.R.O.

Census Return 1851

White's & Kelly's Norfolk Directories.

Norfolk Chronicle.

School Plan P/BG/112, N.R.O.