The Shops That Sold Everything - Robert Bagshaw

For centuries Norfolk's market towns have played a vital role in the social and business life of the county. Neatly spaced out as they were, each one was the focal point for its own area, supplying the needs of the folk who lived in the scattered villages which surrounded it. Lacking present-day mobility, the journey into town was accomplished on foot or by bicycle, with the more fortunate ones travelling by horse-drawn transport. Once there, however, everything they could possibly want was readily available.

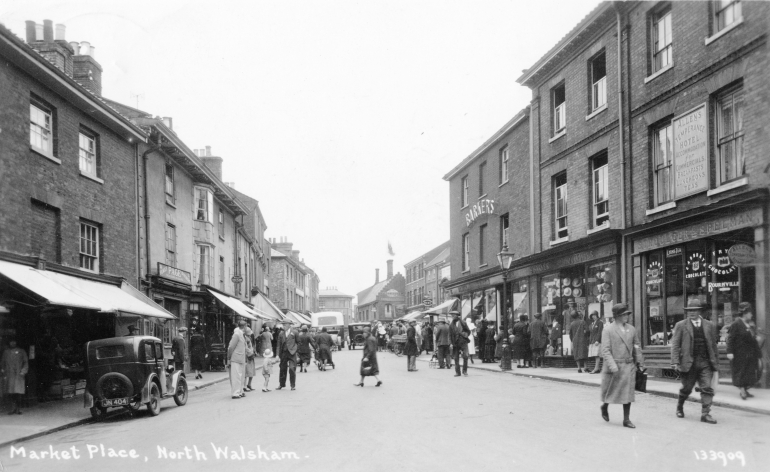

North Walsham was typical of such towns, offering a great diversity of shops and business premises, many of them huddled around the ancient market place which, history tells us, was originally the Lord of the Manor's Home Farm. It had been the arrival of the Flemish weavers and the prosperity they brought with them that made it more profitable to rent out the land for market stalls, which eventually became permanent buildings. And there they have stood, through the centuries, serving the people of the town and its hinterland.

Historically, the width of a medieval stall was seven feet, and although I have not personally investigated the matter, I am reliably informed that the frontage of many of today's shops around the market place can be measured in multiples of seven feet.

The great thing about the shops of my boyhood is they were nearly all completely local - family businesses, owned and operated by people who lived among us. There were, it is true, a few exceptions. The International Stores and the Star Supply Company faced each other across the market place. There was the British and Argentine Meat Company and also Brenner's Bazaar (later Peacock's and eventually Woolworth's), but most of them, large and small, were run by people we knew.

One feature was the absolute plethora of "little" shops, so numerous that one wonders how they all managed to make a living, but each of them small enough to require a staff of just one person - the owner.

Ladies like Connie Peacock, Lily Bruce and Martha Harvey, for instance, supplied the town's smoking needs. Jimmy Craske and George Howlett purveyed a wide selection of fish, while John Hall and Harry Carpenter offered fruit and vegetables. Billy Mount and Albert Kimm would repair your boots - and Frank Chittock would cut a piece of leather to size so that you could do it yourself.

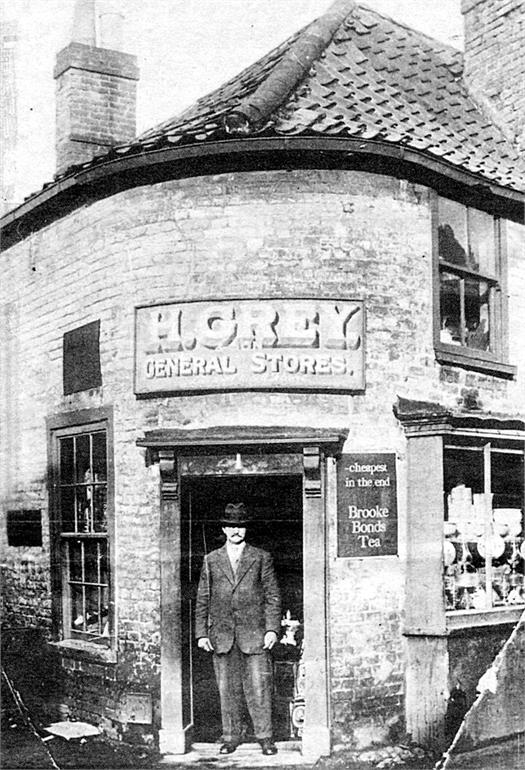

The list was endless, but one will live forever in blessed memory - Mr Grey's "shop that sold everything". Kelly's Directory listed his business as "Hardware and furniture dealers, tobacconists &c." It was that final &c that told the full story, for there were few items which could not be obtained from Mr Grey. From doormats to paraffin lamps, chamber pots to dinner services and every other conceivable household requisite - all were there. There was Lifebuoy soap for bath night, Sunlight for washday, and Monkey Brand for scrubbing the kitchen table, not forgetting Robin starch and bluebags. There was flour and paraffin, vinegar and sugar, tobacco and tea, both Brooke Bond and the local favourite, Lambert's BOP.

If one wondered how that little shop on the corner of Bacton Road and Back Street could hold it all, the sight of his delivery cart was even more amazing. Every day Mr Lawrence from Felmingham took the vehicle out, laden to overflowing, on his trips around the surrounding area. His main cargo was paraffin, with everything else stacked precariously above and around the tank. Items of food tended to acquire an added flavour because of the proximity of the oil, but nobody seemed to bother. Mr Lawrence was just one of a legion of paraffin men who daily made their journeys around the country roads of Norfolk in the service of local housewives.

It would be impossible to write of Mr Grey's shop without mention of his annual sale. It was not really a yearly event - he had one when ever he had a selection of goods which would otherwise be left on his hands. One of the

regular attractions was wallpaper, which was reduced from something like threepence to a penny a roll. A constant succession of children, despatched by their respective mothers, would arrive with instructions to pick a pretty pattern in pink or blue or what ever colour Mother fancied. It was always a single roll, for it was not destined to adorn a wall - it was new lining paper for the shelves in the pantry.

Arthur Griffin was another man who could supply almost everything, though in a different field. Arthur spent his working life in an Aladdin's Cave of bicycles and spare parts and, when he died in 1991, he could justifiably lay claim to have been the longest-serving shopkeeper in North Walsham. He had started his business in 1924 when he was 14 years old, and he always vowed he would never retire -and he never did.

He first set up business in his parents' house in Vicarage Street, his working capital being the £10 he had managed to save during his schooldays. Four years later he moved to Market Street, on the corner of Mitre Tavern Yard, and it was there he steadily accumulated an awe-inspiring collection of bits and pieces he needed for carrying out repairs. The walls and floor were festooned with wheels and frames, mudguards and every other part of a bicycle, in such a state of disarray that no Mrs Mopp could possibly have attempted to clean the place. Yet Arthur knew where everything" was, and it was a rare occasion when he was unable to supply a cyclist's needs.

There were only two things about Arthur's shop which changed with the passing of the years. One was the lighting system, for in 1928 the establishment was lit by gas mantles, which survived until he "went over to the electric." The other was the bikes he sold. In earlier times they were British-made roadsters which have long since become collectors' items. More recently they were mostly foreign - and Arthur got no pleasure from selling them. He was bemoaning the demise of the British cycle industry when I paid my last visit to him for a chat, not long before he died. "Look at that lot," he said. "Foreign rubbish. There isn't the quality in 'em nowadays 'cause hardly any of 'em are made in this country any more."

But Arthur was that rare creature, a thoroughly happy man. He came smiling through the depression of the 1930s and then the years of war which followed. And he remained a confirmed bachelor - I suppose it could be said he was married to his bikes.

My outstanding memory of Arthur Griffin is of the day when he sold me my first carbide lamp. He offered me a demonstration of the lighting procedure and I watched enthralled as he brought forth a flickering flame which, at the time, seemed an absolute flood of illumination. Later developments such as the dry battery and the dynamo were to reveal the inadequacy of the carbide lamp, but it did at least enable the after-dark cyclist to obey the dictates of the law, even though it was sometimes guilty of behaving in a somewhat temperamental manner.

But to the schoolboy cyclist of that time the carbide lamp was much more than a source of light - it was a status symbol. Its presence on the front of his machine indicated he had at last been granted parental permission to ride his bike after dark - one of the major milestones on the road to adulthood. Yet, sadly, it was a carbide lamp that brought about my earliest brush with the law - and it wasn't even my lamp! Furthermore, by a strange quirk of fate, the incident occurred just outside Arthur's shop.

I remember that it was a Tuesday, for that was always Cub Night and we had all gathered at the wooden hut by the railway embankment just off Aylsham Road. Then, when Gladys Smith, our cubmistress, closed the meeting, seven or eight of us retired to the back of the hut for the ritual lighting of our carbide lamps. It was dark, but all went well - except for Duggie Brown. Whether he got the mix wrong or what else could have caused the disaster I know not, but his lamp caught fire and the flames shot high in the air. There was then nothing to be done except to extinguish it and wait for it to cool down before having another go. But we didn't all want to hang about, so we told Duggie to get on his bike and we'd take him home in convoy. Down Aylsham Road we went like a posse of cowboys with Duggie in the middle in case the town constable was on the prowl. He was a marvellous copper and we all respected him, largely because he knew each and every one of us, and more significantly, he knew our parents.

We turned into Market Street and everything was going according to plan until, suddenly, out of the shadows at the entrance to Mitre Tavern Yard strode the familiar figure of the constable. Up went his hand.

"Right, boys - dew yew stop! Now, Duggie Brown, your lamp in't alight."

"In't it?" said Duggie. "Well, that was a little while ago." He was telling the truth. It had been alight - well alight.

"Well," said the policeman, "if that was alight a little while ago.I can soon find out, can't I?"

At that point he started to peel off his woollen mittens. Of course, we knew what he was about to do, but we daren't say anything. He put his hands forward and clasped them around Duggie's lamp. Needless to say, it was still almost red hot, and the effect was dramatic in the extreme. He shot up in the air and went into a torrent of swearing which seemed to last for about 10 minutes, never using the same word twice. We later reckoned that those few minutes just about completed our education. But we never heard anything more about it - I think he was in a hurry to get home and rub some butter onto his blistered hands.

Of course, that sort of thing could never happen nowadays. I sometimes think that a lot of the fun went out of cycling when we gave up using the carbide lamp.

Robert Bagshaw.

First published in the EDP. 30/09/2006